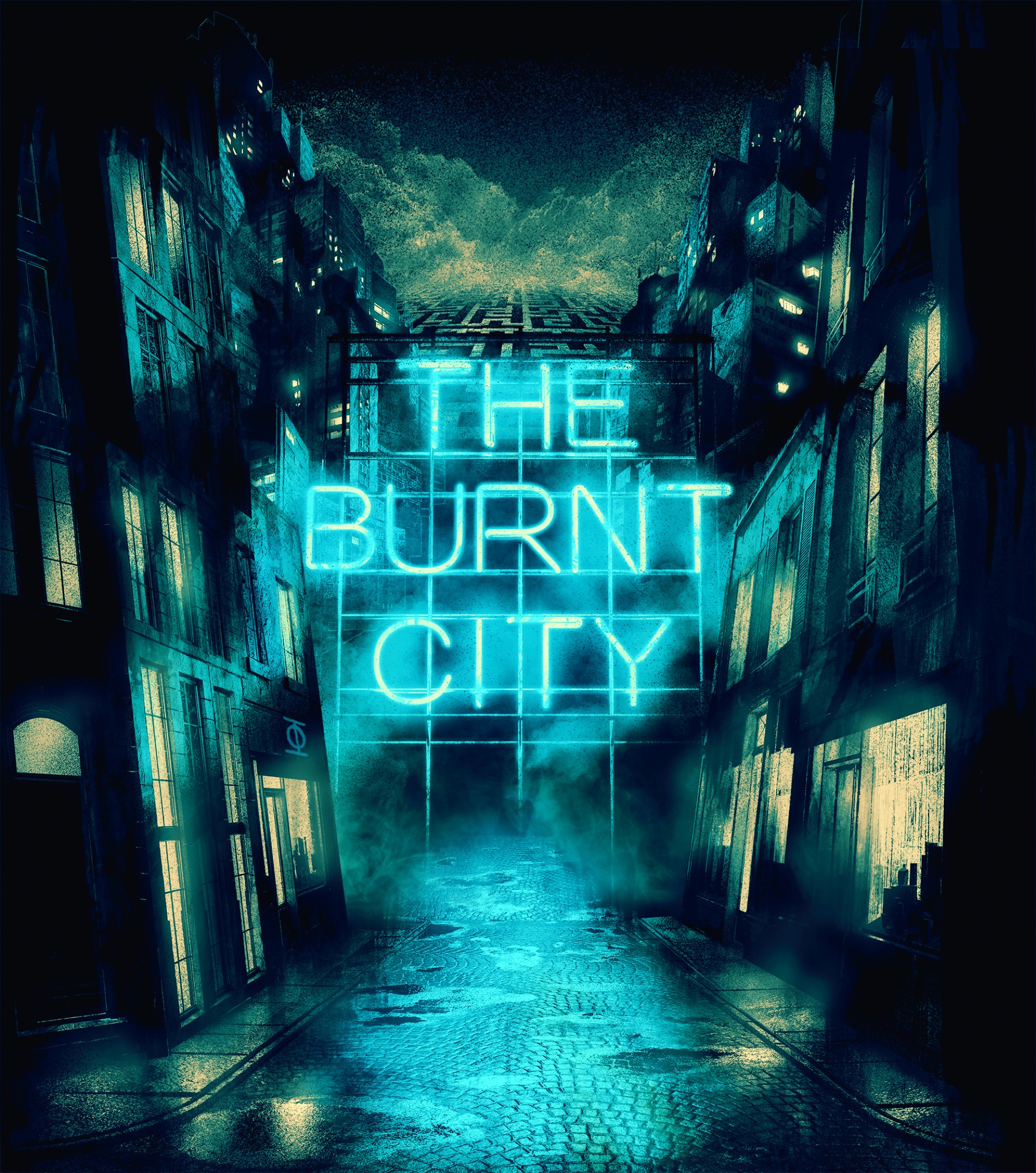

The sky washed with fluffy clouds, was by no means an omen for The Burnt City, a dark, cavernous world. Unlike the sun soaked skyline, and the chittering animated queues, Punchdrunk was eerie, and mythical. Nothing was ever as it seemed, and no story was the same. It was an immersive experience like no other, where theatre, debauchery, and exploration of gender exploded riotously. Like ‘Mulan Rouge’ at The Vaults, the promendade allowed theatre-goers to leave their gender at the door. Here, there were no rights or wrongs as to the way that performers dressed, or gendered language. Instead, there were beautifully choregraphed dances, that were fluid, seamless, yet evocatively haunting.

All pictures by @Punchdrunk

You are not permitted to take any photos or record any videos during the experience.

Choregraphed by Maxine Doyle , the fluidity of the dancers were intoxicating. Few words were spoken, but it did not matter. For the actors narrated the fall of Troy flawlessly, through dance and movement. The sinewy muscles flexed with every step, as they immersed the audience into the devious world of Gods and mortals. But A was getting ahead of herself. Though Greece was teetering on the brink of victory, it was time to take a step back, to the very beginning. They would don beaded masks, bordering on the grotesque. Gloomy white shapes with gaping mouth holes, a device for immersive theatre. Our masks diguised our true identities, minimizing our appearence as spectators. We were all and nothing, different, and the same.

Past the snaking queues we went, into a gallery of antiquities on arrival. A row of ancient vases, headdresses, and libation bowls perched in glass cases precaciously. It was the calm before the storm, a foray into Grecian and Trojan history, and the artefacts that preempted it. Recovered by real-life archeologist Heinrich Schliemann, he excavated the ancient city of Troy, albeit destroying it in the process. It is this chaotic destruction that preludes our intrusion into The Burnt City, entering a cavernous maze of rooms, corridors and floors. Past the smashed final exhibit you go, into the neon backstreets of Downtown Troy. It is Troy like you have never seen it before, an abandoned arcade in a dystopian universe.

In comparison to Greece, Downtown Troy is small, but nevertheless neccessary. You peer into a abandoned shop bathed in Chrismas lights, and spy on 1920’s esque performers sipping martinis in glass windows. The eerie quiet is foreboding, a delectable promise of what is to come. Before you know it, you are in the 1920’s, negotiating a series of winding military camps where people appear to have been conducting experiments based on this discovery, which may or may not have caused the past to bleed into the present. Making sense of history, time or space is futile here. Instead you let it wash over you, imagining The Burnt City, as the Van Gogh of ‘immersive experiences‘. Because as night falls, the city comes alive…

Flitting between the 1920’s, Ancient Greek mythology and futuristic dystopia seems like an impossible feat, but Punchdrunk nails it. The Burnt City is a colossal playground, where non-linear vignettes, are smattered with historical Easter Eggs. There is the killing of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra and the blinding of Polymnestor by Hecuba. The first is perhaps the most powerful, bordering on the carnivalesque. Based on Aeschylus’s play ‘Agamemnon’, Clytemnestra is driven to murder Agamemnon, to avenge the death of her daughter Iphigeneia. In this version Iphigeneia is sacrificed for the sake of success in the war, as well as her mother’s affair with Aegisthus. For the most part though, the history is loose, choosing to bend the boundaries between ‘fact and fiction’.

It is clear that Punchdrunk is part storytelling, part-immersion. The furies watch on as the mortals play out their fate, in a theatrical show that disrupts the norm. Set across three Grade II listed buildings in Woolwich, every detail is spellbinding. Performers dance ritualistic mating rituals, bodies writing in lusty languish. On the other side of the spectrum is desolation and loss, Trojans crying out for avengement, hot, salty tears squelching. A’s interest is piqued, but particularly by the relationship between Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Iphigeneia. Here the masked spectators are taken to Agamemnon’s doomed homecoming, unaware of the fate that would befall him.

Two scenes of note: his wife Clytemnestra cackling on the summit of a tank trap, cleansing her body, and Agamemnon’s death. The first shows insanity, hunger, and deviance, while the latter is a person answering for his sins. A reunion with his murdered daughter in the afterlife, as he dons a jewlled skull mask. The robe traipses down the stairs in a waterfall, slowly cascading. Then of course is the murder of Iphigenia, convulsing in a city of crumbled grandeur. A tale of betrayal, and backstabbing, a sign of blood thirsty times. This storyline is perhaps the most spellbinding, but the non-linear narrative offers endless possibilities. Like adventurers we traipse through the ruins of Troy, embracing, touching, feeling what was left behind. Opened notebooks, and scribblings, unfinished feasts caught on the cusp of decay.

The dichtomy between ‘abandonment’, and ‘celebration’, is a common theme in the ‘recovered city’. It wasn’t just the spectacular acting, or the raw, vunerable choregraphed movements. The set (designed by Felix Barrett, Livi Vaughan and Beatrice Minns) had filmic beauty. Small rooms had intimate aesthetics, personal diaries, scrolls with Grecian poems, rugs, and gilded wardrobes. There was a sense of personalization, a foray into a neglected room, that had whispers of ghosts past, and present.

The sound too was just as spectacular, designed by Stephen Dobbie. The most poignant was of course the adrenalised trance music, that was hauntingly wavering, lilting gently. It was unpolished, and raw, a note caught in time. Lighting, and costume too, were just as flawless. F9, Barett, and Ben Donoghue, controlled the lighting, alternating between 80’s neon brights, arcade nostalgia, and sepia soaked tones of the 1920’s. In Greece lighting alternated between inky midnight blues, and soft sand yellows, showing how light and colour told a story, flawlessly. As a fashion enthusiast, A couldn’t help but marvel at the modern gothic costumes too. Created by David Israel Reynoso, the basques, gold jewellery, and feather boas, were striking. It was moody, yet flamboyant, a future noir drama, where everybody was the star.

Agamemnon is one of the stand out characters in The Burnt City.

Perhaps the biggest theme was the tragedy of female sacrifice, and male violation. It was unnervingly terrifying, parelling a modern world where women still had to think about their safety. A storyline, where women were subjected to cruel torture, abuse, and death. And yet, there was subversion too. Clytemnestra avenging her daughter’s death, and taking back control. Going against societal norms, and choosing her own lover, creating beautifully orchestrated theatre. Iphigeneia confronting her father in the afterlife, a bitter reminder of injustice. Of course, the scenes of male violence are harrowing. The princess bride murdered as an offering atop a giant tank trap, a device for warmongery, and destruction. There are no limits here, and not even family ties will stop the mortals from killing their own flesh, and blood. Like the Gods, they are vengeful, bloodthirsty creatures.

You could say there is little humanity here, but there is smatterings. In Troy, there is bubbling humanity, that is completly devoid in the grandeur of Mycenae, Greece. Though Troy lost, you can see the people that they once were, joyful, and jubilant. In Greece, the world is darker, the devastation of war, cloying. Greece is by far larger, and perhaps more powerful, but in humanity it is lacking. It is a disorientating, dreamlike trance, where you flit between large, open spaces where battles commence, to secret hidden rooms. A juxtaposition between ‘intimate’ and war- life, fleeting human connection in and out of corridor mazes.

It almost seems like you are one of many Hades, the God of the Underworld, where time ceases to matter. History is mixed up, plots become a hodge podge, with no other certainity but a battle for the afterlife upstairs. There is a feast, a brief one at that, supposedly triamphant, a taste of what is yet to come. And yet it comes up hollow, barely fleshed out, there is uncertainity here. The storyline verges on insanity (in the best possible way), and you see the nameless characters draw upon the energy of the God’s shamelessly. Even us, as the unidentifable spectators act differently in the two worlds. In Troy, we are more pushy, nosily thumbing our way through forgotten bedrooms. You hunker down, as you sift through a half-read book, that is well-thumbed, catching a glimpse of the lampshade. You saw before that there was ode to Greece, but now you view the Homeric Hymns.

In Greece however, individuals become cluttered group gatherings, as battle, sacrifice, and violence intermingle with heady lust. There are common themes of bereavement, and deception. Yet, perhaps an overarching theme is a lack of narrative clarity. However A did not mind. She threw her rules, and historical knowledge out of the window, and let Punchdrunk’s wackiness wash over her effortlessly. It almost felt like an animalistic ritual, at times submerged into partial darkness, the audience taunted. Though A was claustrophobic, she didn’t find the experience stifling. Somehow, the darkness, mixed with lighting shifts, created calm, even in the midst of bloody war.

Over in Troy, the Greeks invade using the famous Trojan Horse. Queen Hecuba’s daughter Polyxena is murdered by invaders and strung up, in murderous rage. Like Iphigeneia, Polyxena is the victim of war, two mothers grieving for their slain daughters. It was upsetting to say the least, although Trojan Mythology plays with the idea that Polyxena killed herself out of guilt for Achilles’ death. Nevertheless the story of two mothers bereaving (and attempting to avenge their daughter’ was a better narrative device in The Burnt City. Why? Because she was the Trojan equivalent of Iphigeneia. Like Iphigeneia who was sacrificed so that the Greeks could sail to Troy, Polyxena was murdered at the bequest of Achilles death. His ghost declared that they should sacrifice Polyxena at the foot of the hero’s grave, so they would have favourable winds sailing back to Greece.

Though the show lasted three hours, you realized that the story was being played on a loop. A mesmerizing loop, but nevertheless a repeat. It was time to put the theatre masks down, and impishly shimmer into the cabaret bar, a speakeasy of sorts if you will. Beers drenched in chunky ice, fragrantly light, a cabaret band entertaining the masses. An adult adventure playground, where phones were hidden still, a secret world. You were only here for a short time, but still, you (A), soaked up the atmosphere. It was hedonistic, true, with its flamboyant 1920’s flapper energy, but it was lighter. War was but an imprinted memory, and all traces of Troy, and Greece were scrubbed away. Instead, there were exultant vocals, that bordered on the Epicurean. As the last notes sounded, and the bar switched off its tinny lights, we took a step into the night, and disappeared.

Have You Watched Punchdrunk: The Burnt City?

*Disclaimer

Please note this is a collaborative post, but all thoughts are my own. I was gifted this experience in exchange for an honest review of The Burnt City. Punchdrunk has brought its production back to London after 8 years. It has also been shown in New York, as well.

Leave a Reply