Christmas Through The Ages

‘The witch sets her fire alight reading embers between flames, Druids sat in a circle, watching the sacrificed leap into the flames,On Christmas day the Pagans roast flesh, giving back to the gods who sustain them,Along came the Christians and killed them all, followed Jesus into the world of Christmas cheer, Decadence and wealth at no cost, the king sits on his throne of reverly and jest, You are what you eat is paid no heed as the court plunge into a well of festive debauchery and greed, Mr Grinch and Co turn up their nose at Christmas, banned for 11 years the state is silent, Jolly Charles II marched into 1660 gave the patrons what they wanted-Christmas is back!Dickens clasped a bauble to his chest and Santa slid across the sky into modern day’

AD

Christmas or Yuletide is a Pagan and Christian celebration that derived from ‘Dies Natalis Solis Invicti’ otherwise known as ‘the birthday of the Unconquered Sun. Dies Natalis Solis Invicti was a festival inagurated by Roman emperor Aurelian who ruled during 270-275 AD and celebrated the sun god on the 25th december, as a form of winter soltice to approve blessings from the god. Christians believe that the winter soltice was a hedonistic version of ‘true Christmas’ spirit and later replaced it with a religious observation of Jesus’s birthday who was connected to the solar system as the ‘sun of righteousness’ mentioned in Malachi 4:2 (Sol Iustitiae).

Ra The God Of The Sun ©Metalsucks

Middle Ages & Tudor

It was not until the ‘High Middle Ages’ that Christmas gained popularity in medieval society. The early Middle Ages was centred around the image of the three wise men or ‘Magi’ which offered Epiphany to followers of Christ. But the early Medieval calendar was based around ‘Christmas-related Holidays. Key biblical events included the ‘Forty days of St. Martin’ which began on the 11th November and the ‘Twelve Days of Christmas’ which correlated with the Saturnalian attatchment to ‘Advent’. By 800 the crowning of Emperor Charlemagne on the 25th December led to the renewed popularity of Christmas day.

A modern interpretation of The Three Wise Men ©Subversity

During the High Middle Ages King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which twenty-eight oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten. The Yule boar was a common feature of medieval Christmas feasts, alongside ivy, holly and royal masque balls. King James I enjoyed countless Christmas balls, where the court engaged in games such as cards and masquerades. The Stuarts and Tudors in particular were famed for their decadent revelery and many townspeople would travel days to observe the feast during Christmas time. During Henry VIII’s reign carolling became popular and the introduction of turkey as a national Christmas dish increased in popularity, a welcome change from the tough game that patrons and royalty normally ate.

Portrait of King Richard II ©Flickr

Puritan

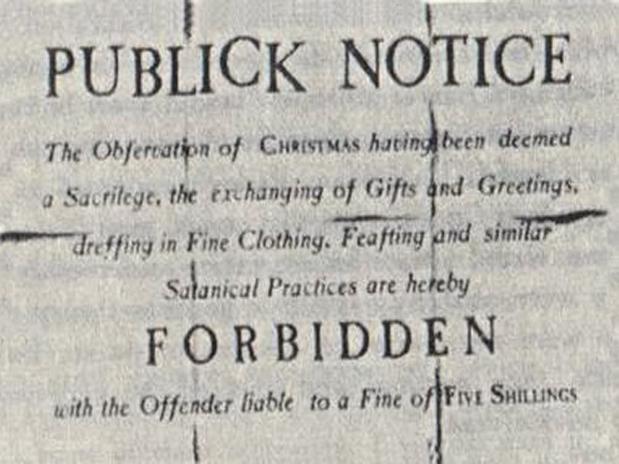

During the Commonwealth period Oliver Cromwell banned Christmas in 1647, disapproving of its ‘oestentious nature’ and affiliation to the Catholic church. The Puritans were against ‘papish’ traditions as it denied all calvinist values and traditions that they followed as impeachable Puritans. Having overthrown the monarchy in 1649 the Puritans believed that they had the best interests of the common people and by ‘banning Christmas’ they could teach them to be less ‘materialistic’ and better ‘wholesome’individuals. During 1647 the people rioted, with notable Pro-Christmas rioters controlling the majority of Canterbury by brandishing royalist slogans and fighting to reclaim control of the festive season. The restoration of King Charles II in 1660 ended the ban but many calvinist clergymen rejected the importance of the Christmas holiday.

Notice used by Oliver Cromwell to ban Christmas ©YankeeMagazine

Victorian

After the image of a true Christmas being destroyed during Cromwell’s reign Charles Dickens portrayal of Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration in ‘A Christmas Carol’ helped revive the true spirit of Christmas. Charles’s Dicken was famed for tackling social, economical and political issues

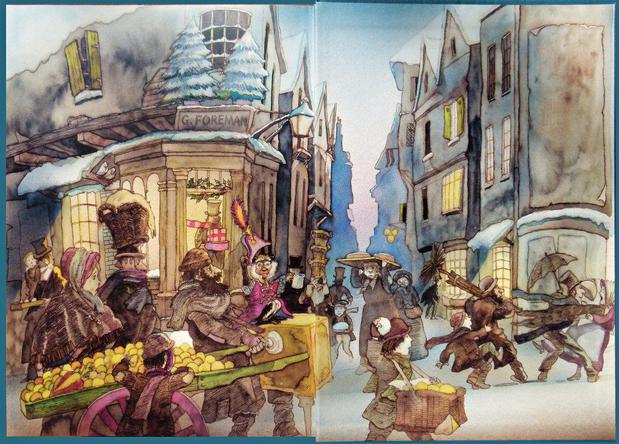

In the early 19th century, writers imagined Tudor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration. In 1843, Charles Dickens wrote the novel A Christmas Carol that helped revive the “spirit” of Christmas and seasonal merriment. Its instant popularity played a major role in portraying Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion.

Back cover illustration of ‘A Christmas Carol‘ ©Scotiana

Modern Day

Due to the diversity of cultures Christmas has transcended its traditional values and beliefs with many celebrating it for materialist or communal reasons rather than for religious observation. A need to ensure that our multi-cultural state observes the traditions of other cultures has left Christmas in the UK open to interpretation.

Decorations

Decorations are both a Pagan and Christian tradition; in the 15th century Ivy symbolized the resserection of Jesus, while its thorns and red berries represented the cruxification of Jesus and the sacriledge of blood that was spilt when he died. In Pagan folklore the ivy was a symbol of fertility and was used by Pagan women in nature spells and fertility ceremonies. In Europe Ivy was used to ward off evil spirits that were ‘conjured’ by heathen witches who were in reality old women who lived alone. Tied into the theme of the supernatural Ivy was believed to possess magic powers that would strengthen the wearer and their ability to wield authority.

Poison Ivy ©Ankou Photography

After the death of Christ colours took on a central role in defining Christmas and red and green were associated with the sacrifice of Jesus Christ after he was sacrificed on the cross. Red alluded to the spilling of innocent blood while the green emblemized eternal life. A secondary colour associated with the image of a traditional Christmas is gold associated with the annual visit of Magi who came bearing gifts of ‘Gold, incense and myrrh’. Gold is a symbol of royalty and became the forefront of every court celebration from the Middle Ages. Gold was a rare metal and was not available to the masses until the 1950’s where gold became synthetic to target a wider audience.

Perhaps the most prolific emblem of Christmas day is of course the Christmas tree believed to have originated in winter soltice. Pagans celebrated winter soltice with ‘evergreen boughs’ and ‘fir’ a symbolic reference to the afterlife and trinity. Æddi Stephanus, Saint Boniface (634–709), who was a missionary in Germany, took an axe to an oak tree dedicated to Thor and pointed out a fir tree, which he stated was a more fitting object of reverence because it pointed to heaven and it had a triangular shape, which he said was symbolic of the Trinity. By the 18th century Germans cemented the modern Christmas tree tradition and transported it over to the UK via Queen Charlotte wife of George III.

A Modern Christmas tree ©Marldon Christmas Trees

Santa Claus

Known as the ‘gift giver’ in Western cultures Santa is a figure with legendary historic and folkloric origins. Santa Claus is made up of three ancestors: Father Christmas, the Dutch figure of Sinterklaas and Saint Nicholas the historical Greek bishop and gift-giver of Myra. As Western culture moved beyond the pagan rites of winter soltice celebrations, traces of Germanic Pagan figure Odin defined the prominience of Santa Claus whose ‘ghostly procession through the sky’ during Yuletide influenced Santa Claus’s journey by sleigh in Western culture.

Santa Claus ©Visit Pembrookshire

What are your thoughts on the origin of Christmas and if you could choose an era to relive Christmas which would it be

Leave a Reply